Fela Kuti becomes first African to get Grammys Lifetime Achievement Award

Recognition of late Afrobeat pioneer and political radical is the ‘anti-establishment being recognised by the establishment’.

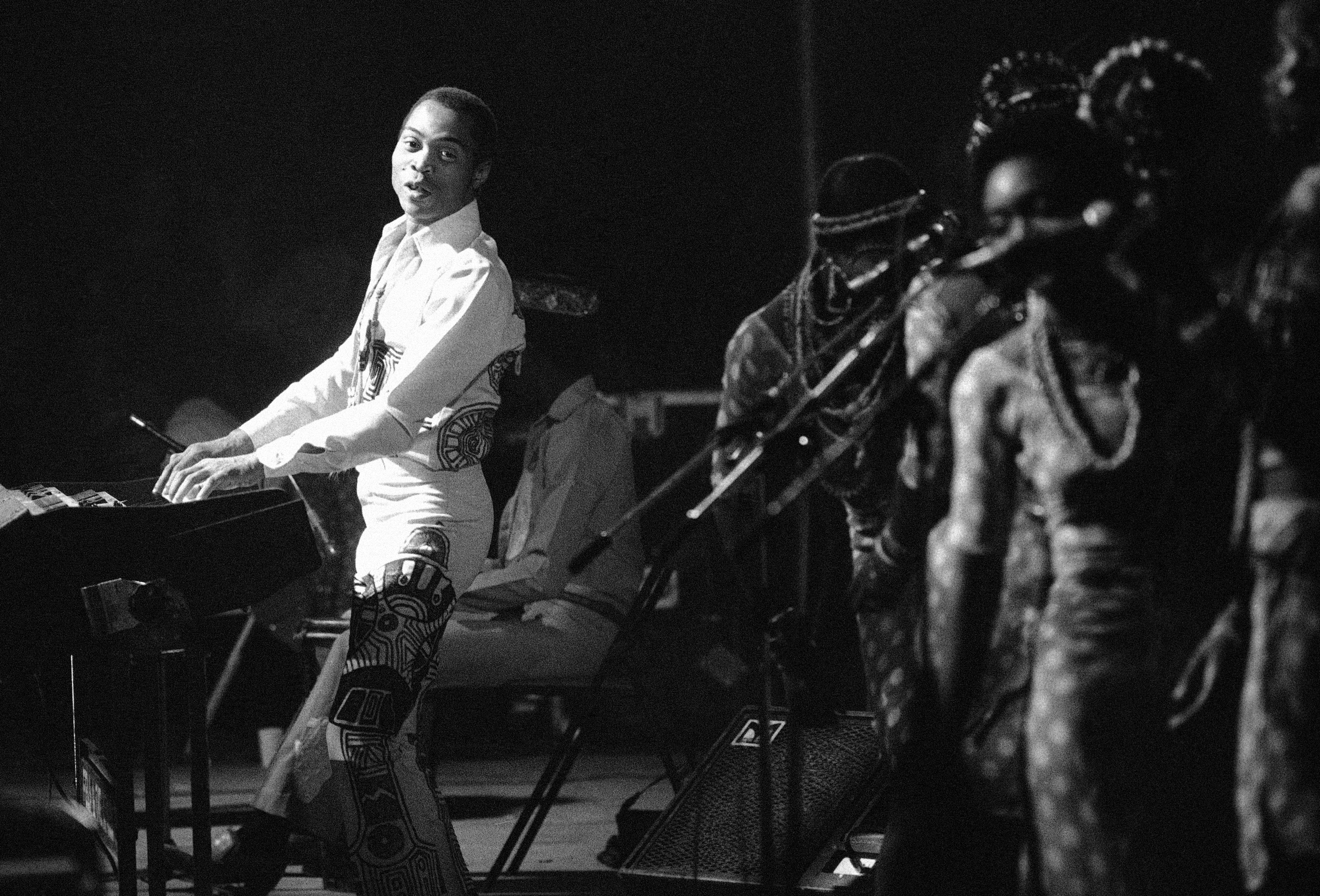

Three decades after his death, the ‘father of Afrobeat’ Fela Kuti has made history by becoming the first African to get a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Grammys.

The Nigerian musician, who died in 1997, posthumously received the commendation along with several other artists at a ceremony in Los Angeles on Saturday, on the eve of the 68th Annual Grammy Awards.

Recommended Stories

list of 3 items- list 1 of 3How not to decolonise the Grammys

- list 2 of 3Diggers and dreamers: Vinyl collectors in Africa’s city of gold

- list 3 of 3Nigeria’s Dancer For Change | Close Up

For his family and friends – some of whom were in attendance – it is an honour they hope will help amplify Fela’s music, and ideology, among a new generation of musicians and music lovers. But it is an acknowledgement they also admit has come quite late.

“The family is happy about it. And we’re excited that he’s finally being recognised,” Yeni Kuti, Fela’s daughter, told Al Jazeera before the ceremony. “But Fela was never nominated [for a Grammy] in his lifetime,” she lamented.

The recognition is “better late than never”, she said, but “we still have a way to go” in fairly recognising musicians and artists from across the African continent.

Lemi Ghariokwu, a renowned Nigerian artist and the designer behind 26 of Fela’s iconic album covers, says the fact that this is the first time an African musician gets this honour “just shows that whatever we as Africans need to do, we need to do it five times more.”

Ghariokwu said he feels “privileged” to witness this moment for Fela. “It’s good to have one of us represented in that category, at that level. So, I’m excited. I’m happy about it,” he told Al Jazeera.

But he admits he was also “surprised” when he first heard the news.

“Fela was totally anti-establishment. And now, the establishment is recognising him,” Ghariokwu said.

On what Fela’s reaction to the award would have been if he were alive, Ghariokwu says he imagines he would be happy. “I can even picture him raising his fist and saying: ‘You see, I got them now, I got their attention!’”

But Yeni feels her father would have been largely unfazed.

“He didn’t at all [care about awards]. He didn’t even think about it,” she said. “He played music because he loved music. It was to be acknowledged by his people – by human beings, by fellow artists – that made him happy.”

Yemisi Ransome-Kuti, Fela’s cousin and head of the Kuti family, agrees. “Knowing him, he might have said, you know, thanks but no thanks or something like that.” She laughs.

“He really wasn’t interested in the popular view. He wasn’t driven by what others thought of him or his music. He was more focused on his own understanding of how he should impact his profession, his community, his continent.”

Though she believes the award may not have meant much to him personally, she told Al Jazeera that he would have recognised its overall value.

“He would recognise the fact that it’s a good thing for such establishments to begin the process of giving honour where it’s due across the continent,” Ransome-Kuti said.

“There are many great philosophers, musicians, historians – African ones – that haven’t been brought into the forefront, into the limelight as they should be. So I think he would have said, ‘OK, good, but what happens next?’”

‘Fela’s influence spans generations’

Fela was born in Nigeria’s Ogun State in 1938 as Olufela Olusegun Oludotun Ransome-Kuti (later renaming himself to Fela Anikulapo Kuti), to an Anglican minister and school principal father and an activist mother.

In 1958, he went to London to study medicine, but instead enrolled at Trinity College of Music, where he formed a band that played a blend of jazz and highlife.

After returning to Nigeria in the 1960s, he went on to create the Afrobeat genre that fused highlife and Yoruba music with American jazz, funk, and soul. That has laid the groundwork for Afrobeats – a later genre blending traditional African rhythms with contemporary pop.

“Fela’s influence spans generations, inspiring artists such as Beyonce, Paul McCartney and Thom Yorke, and shaping modern Nigerian Afrobeats,” reads the citation on the Grammys list of this year’s Special Merit Award Honorees.

But beyond music, he was also a “political radical [and] outlaw”, the citation adds.

By the 1970s, Fela’s music had become a vehicle for fierce criticism of military rule, corruption, and social injustice in Nigeria. He declared his Lagos commune, the Kalakuta Republic, independent from the state – symbolically rejecting Nigerian authority – and in 1977 released the scathing album, Zombie, with lyrics that painted soldiers as mindless zombies with no free will. In the aftermath, troops raided Kalakuta, brutally assaulting its residents and causing injuries that led to Fela’s mother’s death.

Frequently arrested and harassed during his life, Fela became an international symbol of artistic resistance, with Amnesty International later recognising him as a prisoner of conscience after a politically motivated imprisonment. When he died in 1997 at age 58 from an illness, an estimated one million people attended his funeral in Lagos.

Yeni – together with her siblings – is now custodian of her father’s work and legacy. She runs Afrobeat hub,

the New Afrika Shrine in Ikeja, Lagos and hosts an annual celebration in Fela’s honour called “Felabration”.

She remembers growing up with her larger-than-life father as something that felt “normal”, as it was all she knew. But “I was in awe of him”, she also says – as an artist and a thinker.

“I really, really admired his ideologies. The most important one for me was African unity … He totally worshipped and admired [former Ghanaian President] Dr Kwame Nkrumah, who was fighting for African unity. And I always think to myself, can you imagine if Africa was united? How far we would be; how progressive we would be.”

Reflecting on Fela’s legacy, artist Ghariokwu says most big Afrobeats musicians today have been influenced and inspired by Fela’s music and fashion.

But he laments that most have “never really sat down with the ideological part of Fela – the pan-Africanism – they never really checked it out”.

For him, Fela’s Grammy recognition should say to young artists, “If someone [like Fela] who was totally anti-establishment can be recognised this way, maybe I can express myself too without too much fear.”

Yeni says that through Fela’s work and life philosophy, he wanted to pass a message of African unity and political consciousness on to young people.

“So maybe with this award, more young people will be drawn to talk more about that,” she said. “Hopefully, they will be more exposed to Fela and want to talk about the progress of Africa.”