The Take: From a refugee family to Nobel Laureate: Omar Yaghi’s story

Nobel laureate Omar Yaghi on how humble beginnings fueled breakthrough science against the climate crisis.

Nobel laureate Omar Yaghi joins The Take after winning the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), materials that can capture carbon and store hydrogen. Born to a Palestinian refugee family in Amman, Yaghi tells the story of how hardship shaped his imagination, from getting fresh water only once a week to inventing systems that pull water from desert air.

In this episode:

Recommended Stories

list of 4 items- list 1 of 4The Take: Why is Venezuela ‘uninvestable’ for Big Oil?

- list 2 of 4The Take: Iran, Trump, and the deadliest crackdown on protests yet

- list 3 of 4The Take: What Aleppo’s fighting reveals about Syria’s fragile peace

- list 4 of 4The Take: Inside ICE’s deadly ‘surge’ in Minneapolis

- Omar Yaghi, Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, Professor at the University of California, Berkeley and Atoco Founder

Connect with us:

@AJEPodcasts on X, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube

Full episode transcript:

This transcript was created using AI. It’s been reviewed by humans, but it might contain errors. Please let us know if you have any corrections or questions. Our email is [email protected].

Malika Bilal: Today, the molecules of a Nobel Laureate’s life.

Professor Omar Yaghi: I feel like I’ve gone from scarcity to abundance through science. That’s really the beauty of a scientific endeavor and dedicating oneself to science.

Malika Bilal: How Professor Omar Yaghi fell in love with chemistry and how his background as the son of Palestinian refugees led him down this path. I’m Malika Bilal, and this is The Take.

Malika Bilal: Hey everyone. Before we go on with today’s show, remember to leave us a comment telling us what you think about this episode and what you learned about chemistry. If you’re listening on a podcast app, leave us a review telling us where you’re listening from and give us a five-star rating while you’re there. It really helps to show thanks.

Professor Omar Yaghi: I am Omar Yaghi and I’m a professor of chemistry at University of California, Berkeley.

Malika Bilal: Professor Yaghi, welcome to The Take and congratulations on becoming a Nobel Laureate in chemistry. It is such an honor to have you here.

Now, the Nobel Committee awarded this coveted prize to you and two other chemists, Susumu Kitagawa and Richard Robson for what had called groundbreaking discoveries that may contribute to solving some of humankind’s greatest challenges.

At the heart of these discoveries are molecules, the building blocks of life, everything alive and unalive. So before we get into the science, I want to start with the building blocks of your life as the son of Palestinian refugees who were forced to flee in 1948.

Because last month you stood on one of the biggest stages in the world at the Nobel Prize Banquet in Sweden, and you talked about why that might have been unlikely at one point.

Professor Omar Yaghi: I grew up in Amman, Jordan in a refugee family of 10 children. In a home with no running water and no electricity. Sharing our space with livestock, our family’s livelihood. Hardship was everywhere. My chances for success were slim, except for the surprising ways nature reveals itself and helps us overcome.

Malika Bilal: What did it mean for you to celebrate this moment by anchoring it in your childhood?

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Professor Omar Yaghi: Well, it’s a very complex feeling to be standing there giving speech to the, uh, attendees of the ceremony. Of course I am honored by this recognition. I am one of very few people in the last hundred years who’ve gotten this prize. And, my immediate feeling is that the hard work that we have put in, since I was a child, finally is rewarded. And as you mentioned, I grew up in a refugee home to parents that used to live in Palestine.

My family comes from a small village called Masmiya in Palestine, and we lived as refugees in Amman, Jordan, where I was born and raised. So I have a Jordanian citizenship and Saudi Arabia gave me an honorary citizenship, and I live in the United States where I am a US citizen.

So in many ways, I am a citizen of the world and the science that I do benefits the world and adds to the frontiers of knowledge that the world uses.

And I was born in 1965 and lived a, I would say a very humble life. We lived in a home that had no modern conveniences, one room with all of us in it.

And as a child, I think I was a lot more observant than a lot of other children in that I was a very quiet child watching everything around me going on, not participating in the games that children play and so my siblings and so on playing outside, but I really wanted to be inside.

In fact, at some point my parents were wondering what is wrong with this child? And we asked him to go outside and breathe some fresh air, and he’s just stuck in a corner working on his studies. I think that one of the important things that I learned as a child is in my father’s shop.

One of those occasions that I, that still stick in my mind is that when you did a task in the shop, you had to do it right and you had to do it complete. The other thing that I learned as a child, and again from my father, is that you have to pave your own way. The power of work ethic, the power of thinking independently, and the power of paving your own way and the power of doing the job right and completely, otherwise it was not worth doing.

Malika Bilal: I’d like you to take us back to the moment when you first discovered your love of science as an elementary school student, I believe it was. Skipping out on recess with the other kids to sneak into the library and read. Can you tell us about that?

Professor Omar Yaghi: Yeah, I don’t know what compelled me during our break. The library is supposed to be locked because they didn’t want the kids to go in there and mess it up. And so, I don’t know what compelled me to do this, but I thought, well, you know what, maybe I’ll go in and see, you know, what’s going on in this library. And so, the door was supposed to be locked, and it turns out it’s not locked. I turned the knob and there I opened the door, and I picked up a book. And in that book, I saw molecular drawings. I had no idea what they were. I just knew that there was something interesting about these drawings. I didn’t know they were molecules. And actually, that day was a very interesting day because on my way home, I was thinking about these drawings. I was wondering what they might be. I somehow, I felt inside me that I’ve discovered something very unusual. When I went home that day, I thought I discovered something nobody has ever seen before. Of course, I later learned that these are molecules and they are the constituents of everything living and non-living.

Well, I, you know, as I said in my speech, I was hooked at that time. Nothing could turn me away from them. Even parents that wanted me to be a medical doctor or engineer couldn’t turn me away from it.

Malika Bilal: And years later, that’s a good thing, because that experience leads you to the Nobel stage. So Professor, let’s talk about the science that you’ve been awarded for. Your work is developing something called metal-organic frameworks or MOFs. Now I could definitely try to explain it. But I’m sure our audience would rather hear it from the expert. So for those of us who may not have heard about moths until your award was announced, could you explain it as if you were explaining it to someone who has never stepped foot in a lab or excelled in a chemistry class?

Professor Omar Yaghi: Well, the constituents of everything around us is organic or inorganic. Okay. That means mineral base that has metals. That’s the inorganic part. And the organic part has carbon. Okay, so that’s what you think about. What makes up everything around us living and non-living? Well, it’s organic and inorganic.

And these two fields are taught separately and considered as separate divisions, even in chemistry departments around the world. So what we did is we combined these two kinds of molecules together. Just like a child would combine Lego pieces to make different forms.

And so we took the molecules that are everywhere. Millions and millions of possibilities and figured out a way of stitching them together, linking them together through strong bonds to make robust forms. So the Nobel Committee called the molecular hotels. What we built are molecular hotels that have rooms within them and into these rooms.

One can incorporate, can trap molecules such as what we have done, with water, taking water out of the air, out of even desert air to make drinking water. And the power of the chemistry that we developed is not just that we can build different forms of these molecular hotels with different-sized rooms and different-sized openings to those rooms.

But, also we can modify them chemically so that they can be customized for different applications.

So we customize the interior with hydrophilic and hydrophobic sides so that we can trap water from air. We put modules in there that are designed specially to pluck CO2 out of the air and make clean air. We can use the interior with the proper-sized rooms and opening to those rooms to trap hydrogen and concentrate hydrogen so that we can make, uh, clean energy. So that’s in a nutshell, what MOFs are.

Malika Bilal: I love the description of the rooms. The rooms is very descriptive. There’s one other analogy that the Nobel Committee gave that helped me a lot, which was a bag; a member of the Nobel Committee, likened the concept of Hermione Granger’s bottomless bag in Harry Potter. And I’m gonna go even older and say it sounds a little bit like Mary Poppins bag that could fit nearly a whole household. So, to set pop culture references aside, how big are we talking?

Professor Omar Yaghi: Very nice question, and thank you for reminding me to mention this very important property. These rooms when you, let’s say, a MOF material, after you make it, it looks like baby powder or granulated sugar.

Malika Bilal: Hmm.

Professor Omar Yaghi: Imagine that you zoom in on one granule, okay? Just zoom in to the atomic level, you find that it’s riddled with holes.

Those are the rooms that we have been referring to. The more holes you have in this material, the more internal surfaces you are exposing for things to stick on, for hydrogen to stick onto those walls, for water to stick on there, for CO2 to stick on there. And the fact that you can fashion them so that they are selective to whatever you want to bind makes this quite, quite fascinating.

So, imagine now back to the granulated sugar analogy. Now you have each particle, each, uh, component is riddled with holes. Now you have a material that’s full of holes in one gram, which is no larger than a sugar cube, of a MOF.

You have as much space as an entire football field. It’s as if you’ve taken that area of a football field and kept folding it and folding it and folding it onto itself until it was as large as a sugar cube. That’s the space that is encompassed within these materials. So they have extremely high surface area. And when we discovered the surface area, I was absolutely terrified. I mean, I was only, at the time, I was only 30, 31 years old.

Malika Bilal: Wow, making this groundbreaking discovery.

Professor Omar Yaghi: And here I was, exactly, I was going to report this surface area that was six times more than the record, than the previous record that was held by a material that was known for a thousand years.

Malika Bilal: We’ll have more with Professor Yaghi after the break

Malika Bilal: So, Professor, let’s talk about the references, why this matters for the rest of us. Because you’ve talked about what they are and the science that makes them possible.

But you also referenced pulling water from desert air. I know in the past you’ve talked about capturing carbon dioxide from the sky. What does this actually look like in real life? Which of these applications excites you the most?

Professor Omar Yaghi: Well first, I just wanna say that MOFs are beautiful objects. Okay. And I think that’s what originally motivated me to make these. I really didn’t set out to solve society’s problems. I set out to do something beautiful on the molecular level. I think that’s an important point. But once we made them, we had to ask the question, what are they good for?

And so very early on, we started looking at, well, why do they have extremely high surface area? What could we do with this newfound property that is so amazing that broke their previous records of porosity?

And one of the things that we discovered in 2004 was yes, plucking water out of the air. The students showed me this diagram of the behavior of the material taking up water. And I thought, hmm, that seems very interesting in that you could take water out of very dry air, such as would be in the desert, and then take the water out at mild conditions at 45 degrees Celsius, which is really no different than temperature in the desert over the summer. So I thought, well, this could be used for water harvesting to make drinking water.

Malika Bilal: Wow.

Professor Omar Yaghi: And I said in my Nobel speech is that I don’t know if I would’ve seen that in the data that was shown to me had I not lived in the desert before. And so immediately I can see that not only can you pluck water out of the air, but you can also take it out in an energetically favorable way.

In fact, you harvest the cleanest water you’ll ever make is from such construct because the MOF itself, this is not only a material that traps water, but also it’s a filter to water, so it doesn’t allow other molecules that might be, other substances that might be in the air, into the pores. And so, it’s the cleanest water you’ll ever make.

And once mineralized, you could drink it. And, so based on these results, where we also tested in the desert, these tests have been extremely successful, where you can show that the MOF works over and over again, taking in water, water coming out with hundreds of thousands of cycles.

We started a new company called Atoco in Irvine, California which is focusing on commercializing this. And this year, they will show that they have a device that delivers 2,000 liters a day with the most energy efficient setup.

Malika Bilal: Professor, it sounds like you just solved drought. You and I live in a state that is known for it. Is that what I’m hearing? What’s the obstacle to solving drought if not scale?

Professor Omar Yaghi: Yes. I mean, we have created a new source of water and this is not something that people do every day, okay? We have harnessed the power of water that’s in the air through the construction of a MOF that works at low humidity level so that it’s appropriate to take, to create water where you want it in the desert.

And not only that, because the MOF works in the desert, it will also work in areas where you have more humidity in the air, such as, let’s say, Bangladesh or other places that are highly humidified, but where you don’t have clean water.

Malika Bilal: Hmm.

Professor Omar Yaghi: My vision is really to achieve water independence for the individual living on our planet, where you have control over your own water. You have your device, you can put it wherever you want. It can be located anywhere, and it will be harvesting water and delivering water.

Yes. This is revolutionary and it’s cited by the Nobel Committee. I mean, that’s how much this is a big deal.

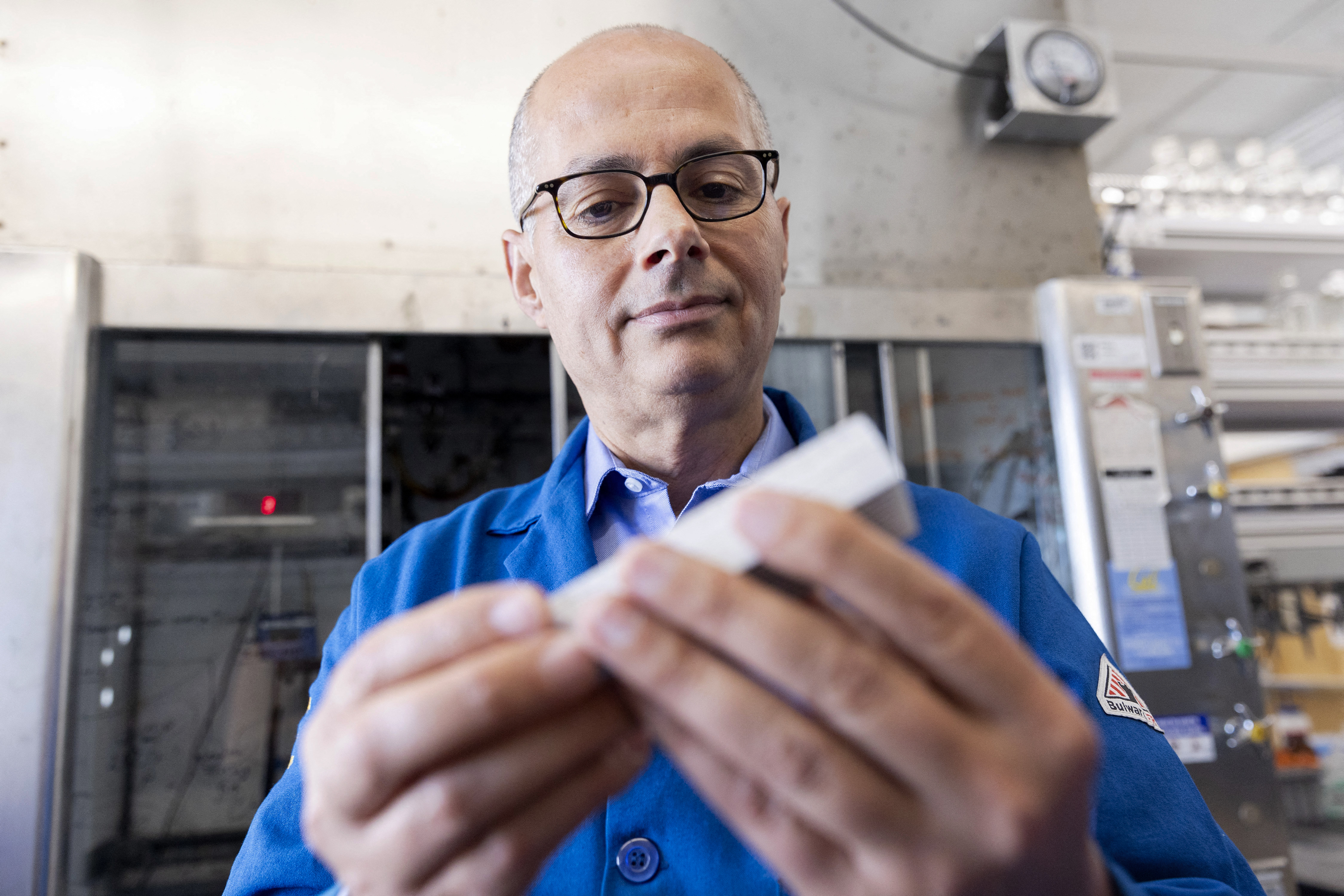

![This photo taken on September 30, 2022 and released on October 8, 2025 by the University of California in Berkeley, USA, shows US-Jordanian chemist Omar Yaghi posing for a photo at the university in Berkeley. Three scientists on October 8, 2025 won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing metalorganic frameworks (MOFs) that can be used to capture carbon dioxide and harvest water from desert air, among other things. [Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small / University of California, Berkeley / AFP]](/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/AFP__20251008__783G863__v1__HighRes__UsSwedenNobelPrizeChemistry-1768597733.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C513&quality=80)

Malika Bilal: Hmm, you touched on it briefly, but I wanna take that discovery, and how groundbreaking it is, and remind people that the seeds for it were planted when you were a child. You tell a story about water and its importance in your childhood memory. What is that?

Professor Omar Yaghi: Well, when I was a kid, water came to our house once every week, sometimes once every two weeks, and only for a few hours. So when you heard the water was coming, you rushed to fill every container you could you have, for that short number of hours.

And so that’s the water that you had for that week or those two weeks.

And if you ran out of it, you had to find a new source of water. And that was not easy or it was very expensive. And so I learned about scarcity when I was a child. These are tough conditions, not just the fact that we all grew up in one room, and had to be there actually with the cattle in the same room and the cattle feed and so on and so forth.

But also that we didn’t have much. I think with the exciting thing about water harvesting and MOFs. Because they present such vast opportunities to address big problems.

I feel like I’ve gone from scarcity to abundance through science. That’s really the beauty of a scientific endeavor and dedicating oneself to science is that you know, is that, yes, my childhood was a difficult childhood. And now, you can see that there are so many opportunities that science has opened up.

Malika Bilal: Well, the example that you shared is impressive in its own right, but it also matters because of the scarcity that you mentioned because of climate change. And in your speech on the Nobel stage, you issued a pretty direct call to leaders.

Professor Omar Yaghi: The hour for collective action has already arrived. The science is here. What we need now is courage. Courage scaled to the enormity of the task. So we may gift the next generation not only carbon capture, but a planet worthy of their hopes.

Malika Bilal: You say the science is here and what’s needed is courage. From where you sit, what does courage actually look like right now?

Professor Omar Yaghi: Well, let me just say that a newborn today will be breathing more CO2 than a newborn a hundred years ago.

Malika Bilal: Hmm.

Professor Omar Yaghi: Okay. We are emitting so much CO2 into the air, I mean, almost 40 gigatons a year. So the question of how do you take CO2? You have to take CO2 out of the air because it’s causing a lot of damage on our planet from melting ice, increasing the ocean levels, to playing havoc with weather patterns where you get more water where you don’t need it, and less water where you need it.

And it’s really affecting our lives and our livelihoods in many parts of the world.

It’s costing the world trillions of dollars every year to address the ramifications of this climate change.

And so then you ask, well, how do you address this problem? We introduce modules that are programmed to pull CO2 out of the air. And yes, the scientific solution is here.

Okay. This material, once scaled, could be placed and into different machines that would be taking CO2 out of the air. So yes, the solution is here. The problem is solved. The problem on the scientific level is solved.

Malika Bilal: Incredible.

Professor Omar Yaghi: We need the global society to come together and understand that this is not just a problem, but it’s a crisis.

When the world says we’ve got a crisis, everybody gets together and they try to fix it. And it cannot be fixed by one country alone. The only way is for many countries to come together and make it a high priority.

Malika Bilal: Hmm. Well finally, Professor Yaghi, you mentioned earlier that you didn’t necessarily do this alone. You credited the students in your lab and those you’ve worked with. So I wonder, what does it feel like to go back to work after winning a Nobel Prize?

Professor Omar Yaghi: For me, it’s very strange because I feel like I have been infused with a new kind of energy to do more. So I went directly back to the lab and with new and more challenging objectives.

Of course it’s the satisfaction of being recognized for long years of hard work and many students that, as I said in my speech, who failed and failed and failed so that they can succeed, going through the arduous process of developing a new field of science. What is to be recognized for that is not only touching, but it’s a forever honor and it’s for the history books to write.

So, I would say that I feel a sense of even more urgency than I’ve ever done before to do something that makes a difference in the world. There’s a lot still to be done.

I think the commercialization of water harvesting and CO2 capture from air being pursued by Atoco, and this is a company that I’m in involved in, I think this is a very, very promising direction. It’s very, very exciting. But also developing the basic science and new basic science for new kinds of materials that are going to even do better and different kind of problems that we are addressing in society is equally exciting.

Malika Bilal: Hmm. Professor, thank you so much for this conversation. You know, I will never look at both a sugar cube and perhaps a molecule the same way after this conversation. I now, I think I can appreciate the beauty in a way I didn’t before. So thank you for that.

Professor Omar Yaghi: Thank, thank you very much. Basic science is about changing the way we think, and I’m glad that you won’t look at a sugar cube the same anymore.

Episode credits:

This episode was produced by Chloe K. Li and Melanie Marich with Phillip Lanos, Spencer Cline, Tamara Khandaker, Kylene Kiang, Sarí el-Khalili and our host, Malika Bilal. It was edited by Noor Wazwaz and Sarí el-Khalili.

The Take production team is Marcos Bartolomé, Sonia Bhagat, Spencer Cline, Sarí el-Khalili, Tamara Khandaker, Kylene Kiang, Phillip Lanos, Chloe K. Li, Melanie Marich, and Noor Wazwaz. Our host is Malika Bilal.

Our engagement producers are Adam Abou-Gad and Vienna Maglio. Andrew Greiner is lead of audience engagement.

Our sound designer is Alex Roldan. Our video editors are Hisham Abu Salah and Mohannad al-Melhem. Alexandra Locke is The Take’s executive producer. Ney Alvarez is Al Jazeera’s head of audio.